Until we started working on our own house back in 2020 my experience with lime was limited to a few isolated instances from my days up at the Centre of Alternative Technology. By the time we have finished the first phase of our house renovation (an architect’s house is never ‘finished’) it was clear that I needed a better grasp of this material if I was ever going to understand and work with older, traditional built buildings.

Lime was being used in some form since we (humans) started trying to shape raw materials into something more than the primitive hut. This material was key in understanding how our ancestors built and maintained their buildings. The buildings most people have now come to cherish.

Lime was used as a ‘glue’ to stick materials like stone and brick together and also as a coating to protect our homes and buildings form the weather. It could be used simply in a practical and rustic way but it could also be shaped and manipulated to form decoration and motif.

Its almost mythical status didn't stop there as whilst it was certainly an effective binder it also had a flexibility to it that allowed the less flexible materials it held together to move and settle without causing bigger structural issues.

It is also easy to repair and adapt; allowing the the reuse of valuable materials. Finally, and probably its best known quality is its ability to ‘breathe’ (a word that doesn't really make sense but thats for another day) or in other words help control the movement of moisture in, through and most often, away from the internal environment.

In my efforts to understand lime I realised I had to get a tad scientific. A grasp on the basic process is essential in understanding how you get from the raw material (typically lime stone, marble, chalk or shell) to the stuff we use to bind and cover building materials.

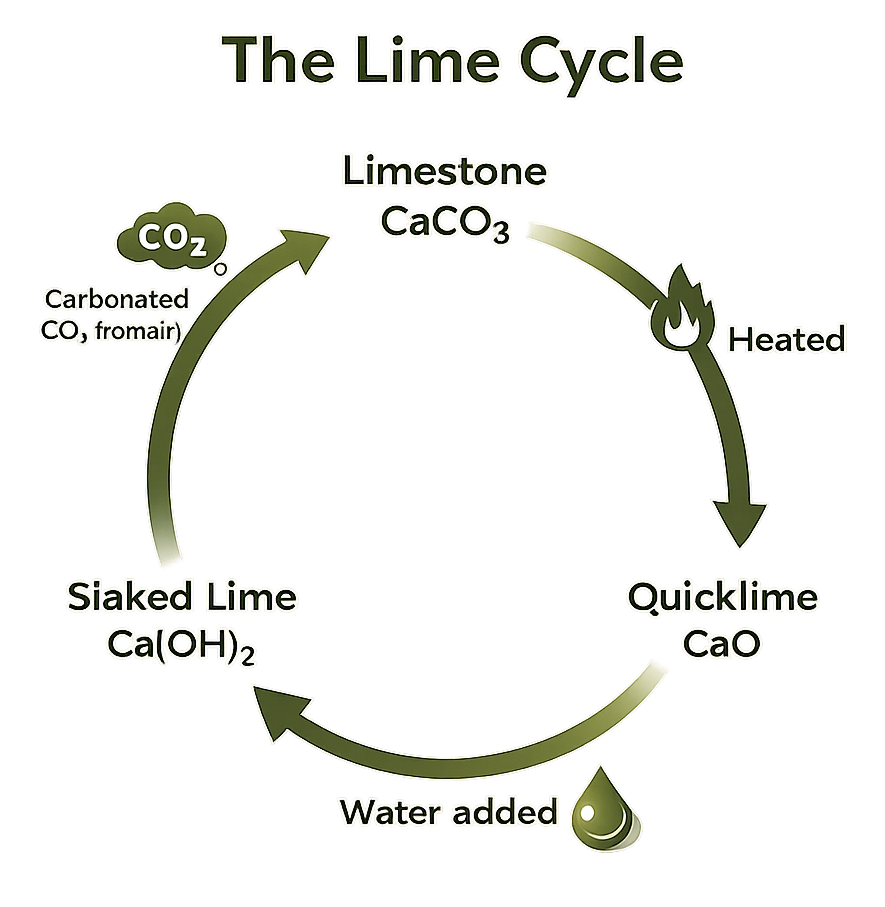

So, the science, the Lime Cycle;

Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) (found naturally in Limestone, Chalk etc) is burnt at over 900 degrees, which just so happened to be the temperature on the surface of Venus - this process expels the Carbon Dioxide CO2 and your are left with Calcium Oxide (CaO) or what is known as Quick Lime.

CaCO3 + heat = CO2 + CaO

The Quicklime is then mixed with water (a process called slaking) to stop it turning back in to Limestone. This gives you Calcium Hydroxide. Which is known as a Lime Putty.

CaO + H2O = Ca(OH)2

The Lime Putty is then mixed with an aggregate (typically sand of various grades depending on what you are going to do with it) and you are ready to use it as a mortar, render, plaster. At this point, as the lime starts to dry out, the finally chemical reaction takes place. The Calcium Hydroxide absorbs the carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air (in a process called carbonation) which gives you Calcium Carbonate and we are back to where we started (chemically at least). Hence why it is often referred to as the lime ‘cycle’.

Ca(OH)2 + CO2 - H2O = CaCO3

All makes sense right? Well this is where it starts to get a little more complicated particularly when we start to look at the different types of building limes including your NHL’s ,’air’ limes, ‘hot’ limes and this is even before we get on to things like pozzalans which bring a whole another chemical process to the mix (literally and figuratively).

However, lets leave that for another journal post and for now just try and get our heads around the basic lime cycle.